Spirituality calls us to be “inclusive” — to treat everyone we encounter with understanding and acceptance, if possible, and especially those quite different from ourselves, for whatever reason. But inclusiveness may be more difficult in Portland than in other cities, especially the inclusiveness that involves different races and peoples.

Spirituality calls us to be “inclusive” — to treat everyone we encounter with understanding and acceptance, if possible, and especially those quite different from ourselves, for whatever reason. But inclusiveness may be more difficult in Portland than in other cities, especially the inclusiveness that involves different races and peoples.

As in the U.S. as a whole, racism towards African-Americans (the subject of this brief history) has been Oregon’s “original sin.”

In 2014, the National Report named Portland as the most racist city in the U.S. And a recent nation-wide survey by the Oklahoma Symposium of Racial Studies also named Portland as the most racist American city. Who? Us? The good white folks of Portland more racist than, say, the white people of Alabama? How can this be? At least in Alabama, whites and blacks regularly encounter each other. Ours is the sin of exclusion, an intentional separating out that goes back to the founding of the state.

In 2016, African-American comedian Kamu Bell came to Portland to investigate gentrification for his CNN program United Shades of America. When he arrived here, he looked around and said, “Where are all the black people?” He called Portland the whitest major city in the U.S.

Not so! According to the book, Portlandness, a Cultural Atlas (2015), Pittsburgh and Minneapolis come in first and second with Portland as only third. But Portland may be one of the most segregated white cities, and that makes a big difference. Dr. Darrell Millner, professor emeritus of black studies at Portland State University, points to a pattern of forced neighborhood segregation (redlining). He says that the black community here, for better or for worse, is “an artificially created community, not a naturally created one.” As we’ll see, Portland’s black community built itself up and then was destroyed over and over again (some say 5 times) by the edicts and policies of the white power structure. Blacks were pushed into undesirable areas of the city; their community was redlined, then intentionally destroyed by urban renewal schemes and a freeway, and finally by a hospital expansion that never occurred. What was once a vibrant black community now appears only on memorial plaques along N. Williams Ave., a former black enclave now gentrifying to such an extreme that even middle class whites can’t afford it.

A Bizarre Contrast

Of course, the racist policies and trends found in Portland have also appeared across the nation: forced segregation, redlining, issues with policing, busing only for black kids, etc. But here, we must admit, these policies have taken some truly bizarre forms. And they’ve also appeared far from the South and in a city known as a haven of progressivism, smart urban planning, and green policies. A city, as satirized by the TV show Portlandia, where young (white) people go to retire. This bizarre contrast — between progressivism and racist reaction — goes back to the founding of Oregon in 1859 and may be one reason Portland draws so many reporters and commentators to the city. We’ve become almost the poster child for a kind of white, hipster racist gentrification. (It’s also worth noting that the TV show Portlandia is filmed in African-American areas of the city but blacks are rarely seen in the show.)

An Exclusionary State

When Oregon became a state in 1859, it inserted black and Chinese exclusion clauses in its constitution and is the only state to have done so. African-Americans were forbidden from working or owning property in the state. (This was officially ended in 1926 but anti-black language wasn’t removed from the Oregon constitution until 2002.) All slaves were free but all blacks had to leave the state on penalty of whipping. And, no doubt, on penalty of even harsher responses. Free blacks couldn’t come to the state, make contracts, or own property. The intent, according to many, was to create a homeland for whites. Again we find that bizarre contrast — a slave-free state in the run-up to the Civil War but one that intentionally excluded black people. No wonder today’s white supremacists flock to the Northwest where they envision (still) a white homeland. (We also have more white serial killers than anywhere else. Could there be a connection?)

Nevertheless, in the early 1900s, nearly 2,000 blacks lived in Portland. They came in with the railroads and had a small community in the now upscale West side near the train station where the men worked as waiters and red caps. As Portland grew, blacks pushed across the river to an inner Northeast district called Albina, causing whites to flee the area in response. In 1919, the Portland Realty Board declared it illegal to sell to blacks anywhere else in the city because that would cause property values to go down. Redlining continued from the 1920s and occurred as recently as the 1990s along with the racially-biased housing discrimination seen today.

The 1920s

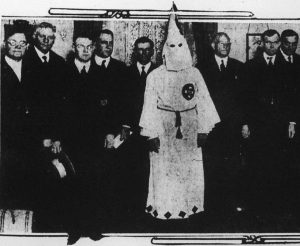

In the ’20s, discrimination was practiced openly. The KKK peaked and elected a governor in 1922. Lynchings occurred. The Golden West Hotel was the center of the African-American community at the time with an ice cream parlor and the Baptist church next door. The community included a haberdashery, grocery, post office, shoemaker, billiard parlor, and saloons. A real community although blacks were still scattered around the area and came together primarily on Sundays.

In the ’20s, discrimination was practiced openly. The KKK peaked and elected a governor in 1922. Lynchings occurred. The Golden West Hotel was the center of the African-American community at the time with an ice cream parlor and the Baptist church next door. The community included a haberdashery, grocery, post office, shoemaker, billiard parlor, and saloons. A real community although blacks were still scattered around the area and came together primarily on Sundays.

The 1930s

One indicator of Portland’s blatant and open racism was the Coon Chicken restaurant which opened on Sandy Blvd in 1931. Patrons entered through the giant head of a black man. Protests were ignored. (Years later, in a bit of “good karma,” the restaurant was turned into a castle and owned by an African-American.)

The Depression wiped out most black businesses because they depended on their black customers who worked as waiters, bus boys, elevator operators, and domestics. Whites took over some of these jobs. Stories are told of African-Americans with college degrees who worked as porters. Some black parents sent their kids east or south to get an education or a profession.

World War II

During the war, thousands of blacks and even more whites migrated to the Pacific Northwest to work in the shipyards. Almost overnight, the black population increased 10-fold in Portland. People came in on special trains called “magic carpet specials.” Due to discrimination, blacks couldn’t find housing in Portland so Henry Kaiser built a new city, a temporary housing project called Vanport which became the second largest city in Oregon. As in the case of Hurricane Katrina, this city was built on undesirable low land in the flood plain south of Jantzen Beach.

Vanport was ¾ white and ¼ black. Housing was segregated (and white housing better constructed) but not the schools and there were some black teachers. Amazingly, the two groups shopped together and some socialized. Later on, people would point to the success of integrated Vanport schools.

In the shipyards, the white unions controlled the jobs, excluded blacks from membership, and relegated them to the bottom of skills and pay. Government anti-discrimination policy was blatantly ignored. Yet the blacks organized themselves, even rowed across the Columbia River to meet secretly at night. And threatened to strike. As a result, they were forced into a separate phony union. Many whites, including the Portland City Fathers, feared that blacks would stay in Portland after the war.

In 1945, a social workers journal listed Portland as the most discriminatory city above the Mason-Dixon Line.

The Vanport Flood

After the war, with a severe housing shortage, 10,000 African-Americans remained in Portland, but 1/3 to a half were unemployed and many were still living in Vanport. On May 30, 1948, the Columbia River flooded and destroyed the town completely. A 12-foot muddy wall came down on the city and 19,000 homes were destroyed in a single hour. Six thousand of them were inhabited by African-Americans. In a strange coincidence, International TS speaker N. Sri Ram arrived just then to give a presentation. Since the airport was flooded, he landed in Salem and took a bus to Portland. While visiting, he gave two talks, one to the public and one to members.

After the war, with a severe housing shortage, 10,000 African-Americans remained in Portland, but 1/3 to a half were unemployed and many were still living in Vanport. On May 30, 1948, the Columbia River flooded and destroyed the town completely. A 12-foot muddy wall came down on the city and 19,000 homes were destroyed in a single hour. Six thousand of them were inhabited by African-Americans. In a strange coincidence, International TS speaker N. Sri Ram arrived just then to give a presentation. Since the airport was flooded, he landed in Salem and took a bus to Portland. While visiting, he gave two talks, one to the public and one to members.

The Portland TS Lodge has historical records going back to the late 19th century. A summary of the year 1948 compiled by TS member George Linton mentions Sri Ram’s visit but there is no indication that the Lodge contributed anything to help the flooded-out victims.

In 2016, Beatrice Gilmore recorded an oral history of her life as a 16-year-old living in Vanport: “This is [Hurricane] Katrina,” she said. “It was the same kind of loss. The lowland that low-income people were forced to live in because it’s the undesirable spot.”

This year, the city memorialized Vanport in the Vanport Mosaic Project, a 4-day oral history, theatre and poetry event. One small unexpected outcome of the destruction of Vanport has been the Kwanzan cherry trees that blossom every year primarily in Northeast and Southeast Portland. More than 500 were planted in Albina in the decades following the flood, part of a larger attempt by African-American community leaders to revitalize their neighborhood — with $1 million in federal funds. True to Portland, there is now a walking tour one can take to see the blossoming cherries.

Not to be overly cynical but Portland seems particularly good at creating these cultural events to mark past discrimination while still pursuing discriminatory policies or simply engaging in systemic neglect.

After the Flood

According to historian K. McCall, the white city fathers, faced with a large number of displaced blacks, developed a long-term plan to force them into the Albina district, “to shuffle them to the nearest area” that had a lot of rundown and cheap real estate so that property values elsewhere wouldn’t suffer. The power structure and the white realtors were quite serious. A realtor was expelled from the association for selling houses to blacks. Other whites helped blacks find housing, but secretly.

In a truly bizarre story, white businessmen wrote to the Urban League in New York asking for an organizational official to come to Portland. When Bill Berry arrived, the businessmen asked him how much it would cost to ship the blacks back home! We don’t have details of the meeting but Berry said he’d stay in Portland only if the group agreed to a goal of integration. They finally agreed and the Urban League was founded with a priority on jobs.

In another contradictory event, a reform mayor, Dorothy McCullogh, passed an anti-discrimination ordinance through the City Council in 1950 but it was repealed at the polls.

Redlining and its Effects

As we’ve seen, redlining appeared early in Portland history along with other efforts to drive blacks out of Portland. Redlining happened across the U.S. and is an effort both to restrict minorities to certain neighborhoods and also to prevent financial investment there. This policy was exacerbated by the 1950s federally-funded urban renewal craze which displaced several black neighborhoods (450 homes razed) to build Memorial Coliseum. The Eastbank Freeway displaced 100 more homes. In the late ’60s, they demolished the heart of the thriving black business district for a hospital expansion that never happened.

And here’s how that hospital fiasco happened. The newly formed Portland Development Commission (PDC) had targeted central Albina as a “slum” and approached Emanuel Hospital to expand there using federal funds from the War on Poverty. All this without any citizen input, 22 blocks razed. Blacks organized into the Emanuel Displaced Persons Association. Residents were given some compensation and 90 days to move. “Negro removal” the residents called it. Blacks scattered to Portland’s East side, “in the numbers”; that is, 100th street and on up where city funds rarely reach. The land was cleared but funds dried up. Years later, Emanuel apologized. And, yes, they erected a memorial plaque.

The beautiful dome that marked the heart of the black business district at the corner of N. Russell and Williams now resides in a park.

In the ’80s, gangs and crack cocaine further ravaged the area.

In 1993, 220 homes and businesses were displaced by the Albina revitalization project approved by the City Council.

Redlining is a vicious cycle which restricts investment in an area and thereby, not surprisingly, forces it to become even more run down. Decades later, the area is labelled as “blighted’. As this cycle played out, the PDC then returned to Northeast Portland and gave $606,000 in grants for new businesses there, mostly condos, boutiques, and bars subsidized by tax breaks to developers and property owners. A plan in 2000 to benefit existing residents was suspended due to a post 9/11 recession.

It gets worse. In 1999, when the Boise neighborhood went from majority black to majority white, neighbors organized to oppose new low-income housing units there.

The Portland Cultural Atlas sums up the process:

Those sixty years saw N. Portland shaped by racism, disinvestment, and neglect followed by urban renewal and rapid gentrification … from a thriving majority-black, majority home owner community … [to the gentrified community we see today].

Ecotopia

Two other events served to fix the image of Portland and the state of Oregon as both progressive and racist. In 1975, in the context of the emerging environmental movement, Earnest Callenbach’s novel Ecotopia appeared. It pictured most African-Americans relegated to city-states within the region, a kind of mass segregation. In 1981, Joel Garreau’s Nine Nations of North America, a non-fiction account, carried a similar message — picturing the Northwest as a “social and environmental paradise where alternative lifestyles flourish” but also “smug and elitist, a bastion of white privilege.” Yet again, that bizarre and disturbing contrast.

The African-American Response

We’ve seen that from the start, the Black community in Portland has been pushed here and there by the political and economic power structures. Yet over and over again they have built a thriving community.

Otto and Verdell Rutherford were important black civil rights activists. The NAACP was housed in the couple’s dining room along (later on) with a credit union. There was a mimeo in the basement where activists lined up to produce the monthly bulletin and the thousands of letters sent to churches, businesses, and the Oregon Legislature. The Rutherford’s house has been called the “cockpit of the civil rights movement.” The couple drove the state’s civil rights movement and they also documented it (now housed as public archives at Portland State University). In 2015, their house on NE Shaver St. was listed by the National Register of Historical places.

All this work paid off. At the state level, younger legislators such as Republican Mark Hatfield (also against the Vietnam War) along with other progressives passed anti-discrimination laws (1953). That was a definite breakthrough although these laws weren’t always enforced. As Otto Rutherford remarked, “we needed white liberal friends because we had too small a population.”

Other progress: Bill Hilliard, who published the African-American Challenger newspaper was hired by the Oregonian in 1962 and was the first black so hired on the west coast. In 1965, Hilliard became assistant city editor and in 1987, the editor of the paper.

In the 50s, Avel Gordly became the first black woman in the Oregon state senate.

Albina became a thriving community in the ’50s and ’60s and its center was the corner of N. Russell and Williams where the building with the beautiful dome stood. In 1963, the Cotton Club, on the so-called “chitlin circuit” brought in such stars as Sammy Davis Jr, Muhammad Ali and others. Yet, in 1967, 15,000 people in Albina lived in only a 2-square-mile area. Some called it an “internal colony.”

Role of Black Churches

As elsewhere, black churches in Portland have been important in the African-Americans community. The Vancouver Ave. First Baptist Church was presided over by Rev. O.B. Williams for 50 years, a man described as a visionary. The church became a central meeting place for the NAACP and the Urban League. Membership was 1200.

In 1964, the Rev. John Jackson arrived to pastor another Baptist church. Described as a great intellect, he was heavily involved in civil rights in the city. Jackson and Williams founded the Albina Ministerial Alliance which is an important presence in Portland today.

The Black Panthers

In addition to the civil rights work of the Rutherfords, the NAACP, Bill Berry at the Urban League and some progressive whites, new organizations sprung up in Portland as the civil rights movement developed across the U.S. The Black Panthers organized in the city and brought Black Power. It was a grassroots movement with almost 50 Panthers in Portland. As elsewhere they promised to defend themselves if necessary. In 1966, the Panthers turned to setting up community programs across the nation. In 1969, Portland Panthers started a free breakfast program that fed 100 kids a day. In 1970, they set up a free clinic with volunteer doctors and nurses, both black and white, and performed 3,000 sickle cell anemia tests. There was also a free dental clinic. Businesses contributed. According to Professor Millner, these alternative institutions were even more threatening to the white power structure.

The FBI under Hoover set out to crush the Panthers and they succeeded in doing so via various means. Here in Portland, they pressured medical people not to volunteer and some businesses claimed they were extorted to donate. In response, the school district set up its own breakfast programs.

Busing arrived in Portland and was applied selectively to black kids. That chapter is long and complicated and, as most of this history, heart-breaking.

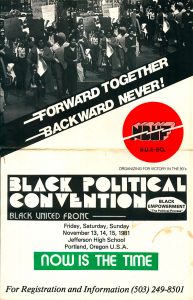

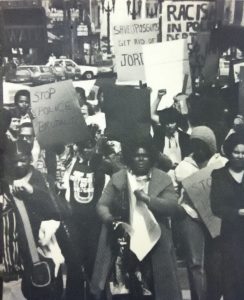

The Black United Front

In 1979, a new organization sprung up in response to busing, lack of black teachers, and other long-term educational ills. The organization was headed by the Rev. Jackson (see above) and a new militant voice Ron Hearndon. The BUF was a melding of religious and militant, older and younger.

In 1979, a new organization sprung up in response to busing, lack of black teachers, and other long-term educational ills. The organization was headed by the Rev. Jackson (see above) and a new militant voice Ron Hearndon. The BUF was a melding of religious and militant, older and younger.

The BUF made demands on the school board but the results fell far short. Blacks staged a successful one-day boycott of schools. In 1982, another boycott occurred involving 4,000 students and that one brought some success when the school board met some of the BUF demands. However, school issues remain to this day.

Police racism erupted in a particularly ugly way in the early ’80s when officers threw 4 dead possums at the door of a black restaurant. The officers were fired but re-instated. Police issues continue to this day and Portland is one of many U.S. cities sued by the Justice Dept. for excessive force especially in regard to people with mental illness.

Police racism erupted in a particularly ugly way in the early ’80s when officers threw 4 dead possums at the door of a black restaurant. The officers were fired but re-instated. Police issues continue to this day and Portland is one of many U.S. cities sued by the Justice Dept. for excessive force especially in regard to people with mental illness.

Black Lives Matter is organizing here. A recently arrived activist describes the racism here as both subtle and overt. People move away from her on the bus, she says. Whites want to touch her hair. (In a lighter moment, Kamu Bell sampled Portland’s weirdness by spending an hour with a “professional snuggler.” As he joked later, “I let a white person touch my hair.”)

Today

Ron Herndon went on to become director of the Albina Head Start Program and still speaks out on issues.

Following comedian Kamu Bell’s visit, some African-Americans pushed back on the narrative of victimized blacks in Portland. Black economist Stephen Green, who helps black businesses get funding, points to the nearly 5,000 black-owned businesses here in 2012. He wants to let people know about American gains in business and community. When folks don’t find a place in the current economy, he says, they create their own. He tweets with Kamu Bell on occasion. He points out, reasonably, that if people don’t know of the existence of black businesses, they won’t succeed and Portland will just get all the whiter. In 2017, Mayor Ted Wheeler appointed Green as oversight manager of the city’s use of a recently passed affordable housing bond.

As the black community disperses, by choice or by economic coercion, it’s more difficult for African-Americans to find black-owned businesses. The website BlackPDX.com by and for black people helps this effort and serves as an on-line resource. Some blogs appear there.

In 2015, a white woman founded the 2-day event, “Support Black Restaurants,” copying a similar San Francisco one. (This happens yearly, on August 27-28). Many thousands have participated. In 2016, Portland Community College started a “White History Month” which at first alarmed many but turned out to be an exploration of racism’s roots. Today, across Portland, high school seniors are completing a “white privilege” survey (with only one complaint).

The number of blacks in Portland is increasing but the number of white migrants to the area is increasing even more. In 2000, African-Americans were only 6.3% of the Portland population.

Six years ago, an African-American woman, Donna Maxey, started a monthly forum, Race Matters, that meets at the Kennedy school.

These are small steps but important nonetheless. “If white people do want to end racism,” the Race Matters leader Maxey says, “they have to understand how it came to be.” That’s our first aim in this Theosophical Society action project on racism. We need to know this history, to be aware of our community and our state.

In a powerful editorial, NY Times columnist Charles Blow sums up what we’ve seen in Portland: that racism is institutional and systemic and made up of many factors: “white flight, the black flight of wealthier black people, community disinvestment, business lending practices, and government policies assigning infrastructure and public transportation to certain parts of cities and not others.”

Laura Lo Forti, one of the artistic directors of the Vanport festival project, moved to Portland from New York. “We’re so segregated,” she remarks. “So many people are invisible.”

Taking Action

If you feel moved by this brief history, consider taking some action steps:

- Keep up to date with these issues in Portland and beyond.

- Support a black-owned restaurant each year on August 27–28.

- Join the Portland TS Lodge as we dine at a black-owned restaurant each year on August 10, the date of the founding of our Lodge in 1911.

—Linda W. Phelps

Sources:

- “Local Color; A History of Portland’s Black Population” Oregon Public Broadcasting,(OPB) 1991

- “Portland Civil Rights; Lift Every Voice”, Oregon Experience, OPB, 2015.

- Portlandness; A Cultural Atlas, 2015

- The Rise and Fall of Vanport; OPB, 2016

- And many articles from the Oregonian

The Theosophical Society in Portland is not responsible for any statement on this website made by anyone, unless contained in an official document of the Society. The opinions of all writers are their own.